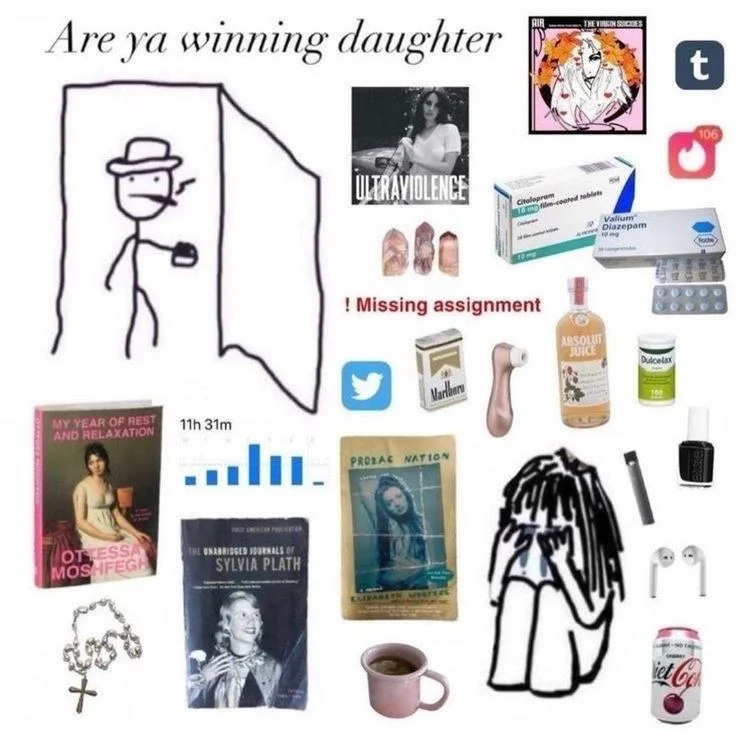

(i can’t find the source for this meme but it is on the interwebs, sorry.)

Something is itching at me. A cultural pattern that builds and goads, gaining traction and becoming ubiquitous very quickly. I’m talking about what I think of as the ‘typification’ quandary, and the often quietly gendered connotations that inflect it. I am talking about the way that social media and pop culture have started to, yet again, designate and simplify what an acceptable performance and embodiment of ‘woman’ is.

Let me explain: I see this trend, in which *everything* ever, especially anything that is popular and associated with women or femininity, is reconfigured into a ‘type.’ The tweets that ironically say shit like: ‘this one’s for the sally rooney sylvia plath phoebe bridgers bisexual ssri bitches” (a type i just made up but i’m sure someone else has also claimed!). These ironic, often witty little statements that *coagulate* (yum) disparate cultural objects or references into a "type” of girl or woman. At first I found these kinds of organizations innocuous and self-deprecating, clever nudges to ‘not take yourself so seriously’ or think yourself a Supremely Unique Individual lest you forget that capitalism thrives on fetishizing individualism and deluding us into believing it’s possible to be a singular, inimitable constellation of interests and sensations. But then I started feeling a lurking irritation every time I encountered this strain of joke—a sensation I couldn’t quite place for a long time.

What I think that odd feeling is, now, is this: we’re at a moment in pop culture that seems to want to arrange, categorize, and typify everything ever under the guise of *not* doing this, of sardonic self-awareness, of pseudo-critical-analysis that, actually, starts to look a lot like our old favorite wolf in sheep’s clothing: misogyny! The reduction and simplification of books, writers, musicians, films, etc, associated with girls or women or femininity of any kind takes the form of a caustic little witticism, one that, in typifying, serves to remind us that no matter what women or girls like, it’s embarrassing, it’s self-absorbed, it’s gauche, it’s frivolous and predictable.

I mean that to say something such as, you genuinely like Sally Rooney—a statement that really feels like a very basic expression of feeling without any particular motive or self-aggrandizement—is to experience the weird, tender pulse of shame. To say that you like or appreciate something that is so often used as a way to engineer categories for ‘types’ of girls or women, even (and especially) by other girls/women, is to say something garish, is to reveal, apparently, how unimaginative and pretentious you are, how much self-awareness you supposedly lack simply in liking something popular and popular, especially, amongst girls.

If you’re a femme person (who covertly-transphobic people often read as synonymous with women, as I myself very well know//esp if you ‘pass’ as cis which is a whole different murky conversation!), or if you’re a woman, or girl, and you like something, anything, you cannot talk about liking that thing without first apologizing for it, without performing a public self-flagellation, almost as a way, it seems, of repenting for the act of liking or feeling something (anything, ever) in the first place. And this dynamic is how the very necessary and productive engine of critique can be manipulated into just another way to perpetuate misogyny, under the guise of ‘self-awareness.’

When your critique actually just feeds into, recycles, and ultimately relies entirely on girls’ socialization—apologizing for everything, for existing—it’s not really a sustainable method of critique. When did I last see a cis man typifying himself, preemptively belittling his own interests and past selves and feelings in order to own them at all?

The phrase “lEt pEople lIIIKE tHINGS” (creative capitalization mine <3) isn’t one I endorse: a Tumblr-y, derivative plea that often arrives as a response to *anything* supposedly ‘sacred’ to pop culture (or to someone’s idea of it) being criticized, usually very justifiably so. “Letting people like things” can be weaponized as a way to undermine and dismiss valid and necessary critique; “letting people like things” is something, more often than not, I hear white people say (esp. white cis men of course) when they’re told that some TV show or book they like is deeply racist or otherwise fucked up and harmful.

I don’t think passive adoration is really adoration at all, in other words. I don’t think that the act of loving something consists of erasing its faults, of making excuses for its every bruise, powdering over every fault-line. That’s just enabling, and I think we can easily enable celebrities, art, music, literature, etc, to exist in a vacuous, unquestioned space, one that lauds and deifies the *thing* in question and thus transforms its substance into iconography. I think that the flurry of fandom can do this, particularly, and have seen it many times. The way that certain people will get free passes and endless defenses (from adoring strangers) for all of their wrongdoing—and how these certain people are usually supported by the logics and institutions of white supremacy, of misogyny and patriarchy, of transphobia, ableism, of capital, etc. This is all true, and complicated, and often deeply reflective of whose voices, feelings, and full personhoods are valued and whose are punished, criminalized, and vilified. I’m obviously not the first person to say this.

On the other side of the ‘let people like things’ crowd, though, is the ‘nothing is acceptable to like; you must critique your own interests and feelings at All Times and recognize that your ‘taste’ is engineered by capitalism and is therefore redundant, stupid, vapid, or otherwise ridiculous; anxious and incessant self-reflexive-critique IS the only worthwhile thing.’

No one says that, exactly, but they don’t need to. It’s not that I disagree with them. It’s just that whenever I see that particular type of argument, I think, well, duh. But life goes on, and there’s not a way to sit inside of a jar and not absorb or take in anything, to lock oneself inside of some mythological vacuum in order to ignore all cultural and societal bullshit and thus actually have ‘free choice.’ Or maybe there is, but it’s not a life I particularly want to try to live.

And, further—I think that the typifying trend is insidious because of how bound up with misogyny the most common expressions of it are. Can we like or appreciate things, not uncritically, as women, girls, femmes, anyone in the realm of what is culturally read as ‘femininity,’ without being told we’re carbon copies of each other, that our interests and proclivities are stupid, are memeably hilarious in their shallowness? And of course, the way white people experience this is vastly different than the way Black and brown women and femmes experience face this phenomenon. Obviously.

In fact, I’d say the ‘typifying’ has an insidious, deeply racist effect—it often reduces the things women and girls and femmes ‘can’ be and do and enjoy into EXTREMELY limited and whitewashed categories. It doesn’t usually effectively critique white visibility or the way pop culture fetishizes white women’s everything, though, I don’t think; rather, this form of typification relies on misogyny alone in order to tell us how unoriginal and mockable all girly shit is.

I’m thinking of a particular essay that made the rounds in 2019 and hasn’t really received what I’d suggest is…maybe some necessary critique, called, “The Smartest Women I Know Are All Dissociating” by Emmeline Clein. I think the piece is well-written and has some undeniable points, but some element of the argument—and what it’s culturally metastasized into—feels underbaked, uneasy to me, perhaps simplifying woman-made art into the very tropes it’s trying to critique. I mean that to watch Fleabag and think that Phoebe Waller-Bridge is making a case for “dissociative feminism” feels like perhaps the wrong takeaway—when I watch Fleabag, I’m witnessing a lesson in self-detonation, in emotional self-harm and the overspill of grief and all the ways we can try to shield ourselves via disconnection, via defensive humor and irony. I mean that it feels kind of reductive, especially when I don’t think works like Fleabag are really trying to make cases for a particular strand of feminism so much as they are trying to explore a particular experience of the constructed, socially envisioned hell of ‘womanhood.’ Fleabag isn’t somehow exempted from blame, from accountability for her suffering and her inability to really connect with most people.

I mean that depictions of “unlikable” or unruly women do feel important—and depictions don’t mean that these are women to be aspirational, to be emulated or followed. Media literacy (a buzzword term, I know!) does feel frail in this regard; I don’t believe in the “separate the art from the artist” redundancy bullshit because it’s almost always used to justify excusing the cruelty and exploitation enacted by cis men and white people. But I also think that we risk losing nuance when we immediately interpret every depiction as an endorsement.

Seeing the way that ‘sad white women’ lit has been discussed just affirms this unease, for me. There’s a difference, I think, between the legitimate, needed critique of how white female sadness/pain can be fetishized, deified, aestheticized and taken seriously (to a point, always to a point) and weaponized in order to enforce white supremacy/why white women’s books about their pain are always the ones made most visible and awarded, and this other phenomenon I see, one thinly veiled as Serious Literary Criticism but really just, yet again, misogyny. For example, when I see people shoving a bunch of women writers into one grouping, labeling them ‘sad’ or ‘angsty’ or whatever variation of those descriptors (and the undercurrent of belittlement and ridicule, of course), I get really frustrated.

Almost always, the writers in question will legitimately, to me, have almost nothing in common, not their writing styles, not the nuances and feelings their work evokes, nothing other than the fact that ‘women’s pain’ will always be made to feel and seem gauche, monolithic, and like a genre in itself, one we can read once and then never again, as if it is a simple and easily digested thing, rather than an infinity room, an endless and multi-hued range in the same way we so easily and lovingly allow white men’s pain to be.

It drives me crazy. To be told that we have enough ‘sad girl books.’ I think, am I reading the same book?! As in: very, very rarely have I read one of these ‘sad girl books’ and felt only easily simplified and pindownable, blank-faced, generic ‘sadness.’ It’s as if women and girl characters are going to be forced into a box no matter what you do—they are either ‘sad’ and therefore annoying/dramatic/wallowing, or ‘unhinged’ and thus overdone/overwrought/garish, or ‘romantic’ and thus vapid/void of depth/hideously naive. That so many teenage girls online seem to buy into this false equation, this tidying of feminized emotions and feelings, is one of the worst elements of this pattern. Literature is comprised of textures, all of them, of senses erupted and set aflame and manipulated and wounded and engorged. Literature is a reflection, a mirror, yes, and to flatten so much nuanced literary work written by women into these reductive little categories, when so many genuinely terrible and profoundly untalented men overpopulate the literary world, well…it’s not doing anything revolutionary, is what I’ll say.

To simplify and reduce women’s work into these categories is another way of telling us that female pain is boring, overdone, and that we somehow have reached our finite quantity of stories that we need to hear about it, as if it is one, singular and universal, identical feeling. I’m not saying to romanticize, or worship femme pain; I spent so much of my adolescence doing just that, and that tendency is a form of self-obliteration and self-violence in its own right, also guided by patriarchy’s need to tell you to fit into a binary, of either sanctifying your pain or dismissing it. I’m saying that it exists, and it will always exist. And that I don’t want to stop reading about it. Of COURSE there are derivative and uninspired, just plain shitty books about women’s pain, about femme pain, about white girl pain, of course. But that doesn’t mean ALL of it is derivative and uninspired. That doesn’t mean that femme-coded pain is inherently silly, overdone, whiny. Especially when the work of so many Black and brown women and femmes is culturally cleaved and simplified as pain-gazing, as trauma-porn, is tokenized in the literary world and “afforded” an inch of space, one at a time.

Isn’t the whole fucking literary canon about white male pain? Isn’t it allowed to be textured, complicated, ever-changing, and how do we never seem to run out of room for it to take up and swallow?

What this discomfort I feel really comes down to, I think, is the fact that social media has developed and romanticized, even while making-fun-of, an intractable tendency to label and categorize people through what they consume.

If you read My Year of Rest and Relaxation, you must be an 'ottessa moshfegh joan didion unhinged tumblrina girl. Thus you are interpreted and read as a ‘type’ of girl, without much doing on your part, necessarily, and can easily be mocked and dismissed for it. It seems there’s no mediation happening, no understanding that a person is not only the things they consume, that someone is not synonymous with a ‘type’ because they happen to like a particular book or musician, and so forth. It’s late capitalism bleeding into the water. It’s ‘self’ as ‘vessel.’ It reinscribes individualistic rhetoric as much as it tries to critique or parody it.

It’s funny, because I think that cis men so often and exhaustingly use a list of things they consume (usually things they don’t read with a critical eye *whatsoever* and aren’t forced to constantly defend in order to consume/like, btw) as a replacement for an actual personality, for a full and multidimensional interior life and capacity to learn about and express oneself. I know no one as addicted to consumption-as-identification as cis white men, specifically. Masculinity can be a hollow, constrictive binary, much like femininity, and it seems that cis men try to fill their meager selves up with now-tired references and their own little biblical dudebro canons without ever trying to develop a single thought of their own. I mean that I think they are not generally socialized to critique—and, frequently, interrogate, self-gaslight, and editorialize/soften—every single action they enact, and thought they have, and interest, and desire, the way that anyone socialized as girls so violently and relentlessly are.

This indoctrination is nightmarish, is self-defeating, self-depleting, and limiting in so many ways, but it makes critique a familiar presence, not one Threatening To Our Very Being and Stability as a Real Person. Cis men are not taught to doubt themselves this way. It’s usually only when/if they like things that are considered ‘feminine,’ of course, that they’ll experience this type of reflexive, unrelenting doubt, and the urging towards its close cousin, shame. Think of the way most cis dudes react to their Most Beloved movies or books being even *remotely* criticized or questioned; the defensiveness, the gasping/theatrical/whimpering why do you have to ruin it for me? or the near-violent excuses and embarrassing rants. I’ve never seen anyone more fragile or brought to rage than a cis man when you critique anything he likes. Because culture is built for white cis straight men, specifically, and the closer you are to that formation of identities, the closer you are to power, to being the exact audience these '“beloved” pieces of pop culture are for. Of course they worship the same shit. They think women’s taste is unoriginal, but theirs is nearly indistinguishable. When the world is built for you, it’s probably hard to imagine that your ‘unique’ tastes are products of capitalism and culture just as much, if not more, than women, or anyone else’s.

I think back to Lili Loofbourow’s now well-known 2018 piece for VQR, “The Male Glance,” in which she painstakingly articulates the cultural tendency—opposite of the male gaze, she argues—that doesn’t fetishize or sexualize women’s art so much as entirely dismiss, trivialize, and overlook it. She notes:

This is the male glance’s sub rosa work, and it feeds an inchoate, almost erotic hunger to know without attending—to omnisciently not-attend, to reject without taking the trouble of analytical labor because our intuition is so searingly accurate it doesn’t require it. Here again, we’re closer to the amateur astronomer than to the explorer. Rather than investigate or discover, we point and classify.

Pointing and classifying—that’s precisely what this typification gesture does, and in doing so, entirely bypasses investigation, discovery, nuance, complexity. There is no appreciation for or interest in the specifics of the work; there is an immediate, reflexive gendering, a this is a feminine piece of art and thus can be registered as a specific type or category of “woman,” of “femme.” This style of critique is structurally abscessed, is without much weight or insight. I wonder if we can read pieces of art not as endorsements of particular cultural modes of being but as depictions, as representations and expressions. I mean that we are literally reducing and simplifying femme art; we are reproducing the same patriarchal classification—Types of Women, as if women need to be read as one thing, as (only, and always, embarrassingly) Sad or Feral or Moody, as taxonomically tidy sets—that we should be working to resist.

Is there a way to occupy “womanhood,” or, in my case, to occupy femme existence, that doesn’t immediately become cliche, basic, unoriginal, whiny, indulgent, silly, overdone? The gender binary still has a stronghold on us, obviously—cisnormativity and transphobia prescribe, prescribe, prescribe, rely on the enforcement of these categories of “woman” and “man,” “feminine” and “masculine,” in order to marginalize and subjugate transness—and this typification feels, to me, like another extension of its poisonousness. I am not suggesting we not critique women’s and femme art. I am not suggesting that at all, just the opposite; that we not rely on typification, on patriarchal reflex, as actual, substantial critique.