You cleave your own heart to bits. But no one asked you to. You compromise. You cut into your own heart, offer up your bones, support, tenderness, sacrificial, self-denying. The roof of your mouth is permanently raw, flayed by the words you crush into piecemeal rather than express anything even remotely resembling a need, a desire. You try so very hard to not be a person, really—to ever let on that you have feelings that can be wounded and want things and hunger for love in the worst and most secret, shame-scarred way, precisely because you don’t think you’re actually allowed to have it. You think: that’s not for me. It’s for everyone else who wants it. But not me.

You, perhaps subconsciously, think being this way—a warm room for everyone else, a reservoir without end, a mirror providing everything but itself—is the only way you can possibly deserve to be here, to exist, to deserve love or anything like it. You think you can become lovable through utility, through smothering every flutter of a need or a want. You cannot just be. You cannot just feel and not justify, explicate, interrogate, invalidate and disavow your feelings. You don’t know how to be that at ease with the world. You don’t know how to inhabit your personhood any other way.

I try to be grateful for my acne. For the ingrown hairs and the patches of red that bloom around my mouth around the time of my period. For the way my guts twist and my uterus bludgeons itself every month, for the blood that keeps coming. I don’t mean that I’m sugarcoating, that I’m indulging in toxic positivity—it’s not that. It’s more nuanced, less aggressive-optimism-and-denial and more a practice of I am alive I am alive I am alive and hungry and greasy and sweaty and bloody and look at this acne, look at this body being alive in the world and all the debris and evidence of living. Chronic illness still fucking sucks and I’d love to not have to try to appreciate anything about it, of course. But still.

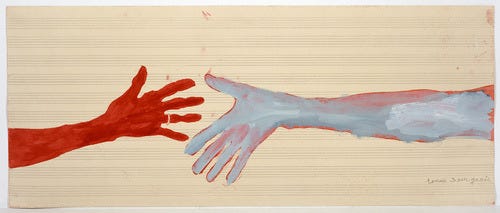

Thinking about death becomes essential, actually, to appreciating anything, especially the neediest parts of me, which I’d usually rather keep locked somewhere dark and silent. Death is the thought that pelts itself at me, insistent: you will be dead one day and you don’t know when, but one day you won’t be able to need anything, to want anything, to be unruly and embarrassing and vulnerable in your admitting to wanting or needing something. Why are you preemptively denying yourself everything, before even reaching out a single shaking hand?

I read part of Amber Jamilla Musser’s Sensual Excess and the book stings, in a generative way, but salt-laced. She writes: “Self-love is not necessarily restricted to pleasure; it requires “ethical management of the self,” pushing the self to be configured in new ways that might be challenging and difficult.”

Pushing the self to be configured in new ways that might be challenging and difficult. The line thaws in my chest, warm water leaking through. It’s not an altogether pleasant sensation, but it’s new, and it’s close to the warm odd muck of birth, I think, in a necessary way. I want to believe that self-love can be a domain of liberation—and that love in this sense doesn’t have to mean constant-admiration or approval, but more like, foregrounding everything you do, all your actions and experiences, in some innate knowledge, that you deserve to be here, that you do not need to earn the right to exist and take up any space at all. Self-love as the knowledge that you do not have to be good. That you, splitting your shins, crawling through ravines, bleeding all over your clothes, is not the exchange you must make for being in the world. What if this new configuration, of the self, means appreciating that you are real, and you are here, and these facts do not make you evil, that you do not need to constantly self-flagellate or self-punish. That you do not need to achieve being alive; that you already are, and you don’t need to hurt yourself into feeling subjugated and pain-torn enough to deserve it.

Friendship—the golden seam between pages of loneliness, existential malaise, dread, immobilization. Acts of care are what I believe in these days. I don’t want to admit it, and I know it’s not conducive to a particularly optimistic politics, but lately all the hope I can summon lives in the smallest, but most essential gestures of care: feeding each other, working within community to supply basic necessities like tampons/pads and diapers and whatever else, filling up fridges, finding ways to fill all of the seemingly endless gaps in every structure that is supposed to “care” for us and fails, keeps failing.

To be chronically ill is one way that this dearth of care, and this incessant encounter with what (queen) Anne Boyer calls the ‘carcinogenosphere,’ or what also might be more loosely called displays of covert and overt biopower by Foucault and co, appears for me. But even my shitty experiences with the pervasive ableism and inadequacy of the healthcare system are mild compared to most—I have insurance, I have access to doctors even if said doctors often do not seem to really listen to me whatsoever, I am white-passing and do not experience any of the structural racism embedded into medicine—and these things should not be privileges by any means, but they are. And so it might sound fatalistic, and I try not to be, truly, but the only manageable form of “hope” I can possibly generate or believe in right now lives in these small gestures of care, of attention to what is lacking and what we can do to make the world a little less unbearable for each other. I want to hope for more than that, of course. But perhaps that’s why I try to follow/support the work and lead of activists, theorists, organizers, who have a more active and consistent relationship to hope—rather than try to photosynthesize a false faith I don’t actually have, not right now.

This is a meandering post. What I’m trying to say, really, is that minute gestures of love are maybe what make the world breathable for any of us, in spite of all of the systems that work to make it as uninhabitable and cruel as possible. Finding mutual aid coalitions, community fridges and kitchens—these actions feel possible and crucial and perhaps unromantic, but I believe there’s actually a romance in these unspoken, unseen moments of mutuality more passionate than any grand gesture.

I return to poetry because we get to listen to the heart there, rather than smother it, second-guess it, dissolve its noises and shudders, no matter how inconvenient the feelings are. So let me borrow from Marie Howe’s “My Dead Friends,” in which she writes,

My friends are dead who were

the arches the pillars of my life

the structural relief when

the world gave none.

It is a lot to ask of our friends:

To be the warm room. To be the structural relief. To be pillars. To be the glue of our lives, when we are not welcome in our own countries or homes, when we are not, in some way, or multiple ways, not generally perceived as fully human. It is a lot to ask. To agree to care for each other in not always necessarily easy or painless ways. There are boundaries, too, that always sprout alongside devotion, that must rein in its flood, keep the water slightly contained.

I am thinking about queer friendship, about the shared trauma and the way it can become addictive, tracing each others’ wounds, over and over, or, sometimes, denying them altogether. I am thinking about history and its everywhereness, especially in friendships. Our histories and the planet’s. It is a lot to ask of anyone. Rethinking intimacy means that friendship is a collaboration in the way that we typically position monogamous romances as. I am thinking, too, of how deep and life-sustaining and ever-fruiting these friendships can be, and often are. How what keeps me afloat is the knowledge that we matter to each other, somehow, even if we’re needing space or solitude or whatever. That there is a thread and we are not letting go.

Friendship, as what can collect debris and construct something more salvageable, more creative and considered than the patriarchal, blood-defined bounds of Western ideas of “family.” Friendship as not any less complicated or passionate or profound or knotty than romantic love.

But the sticky truth that might coat our tongues, no matter how much we insist otherwise, is that some of us do want romantic love. That to deny yourself even the desire for it—when you’ve felt like it’s not yours to have, not yours to experience, that you are somehow fundamentally incompatible with being-loved-in-that-way for whatever reason—is not going to necessarily free anyone, either.

If you grow up entombed in your own shame, locked into the mindfuck of trauma or loneliness or feeling socially abject or altogether alienated from the romantic sphere, you might not feel like you deserve this kind of love. That to even envision it is presumptuous, selfish, fundamentally outlandish. The thought of asking for it, admitting that you want it, can feel like the most unforgivable or embarrassing gesture possible. Admitting that you want that kind of love might feel like you’re voluntarily stepping forth and into a guillotine. Yes: it feels that melodramatic and that masochistic. I think of communal care, even, and sometimes I wish we discussed this more: that we shouldn’t hierarchize different types of love or intimacy above each other, or deify some heteronormative and deeply fucked-up notion of “romance” as a universal salve, but also, maybe not everyone wants to discard the desire altogether. That many of us have never felt entitled to anything but shame, heaps upon heaps of it, smoldering and fecund and intimately familiar. That a continuous denial of our own desire might not be inherently liberating, either.

What am I trying to say? I’m not sure, exactly. Maybe this Substack is just my now-flooding emotional reservoir, maybe I’m just rambling, maybe none of this coheres. But there’s so much to say about intimacy, and the capacity to admit that you might want it, and how, exactly, do we ever nurture it correctly or adequately, in the right ways? How to not mistake one’s own tendency to overcompensate, to fawn, to provide emotional refuge, to overpour, to in fact play the role of emotional support animal, for actual mutual vulnerability and intimacy? How to unlearn this calcified conviction, that intimacy, love, care—all of it—is always conditional, always contingent upon our earning it, our breaking and bleeding out our own hearts for it?

I always, always return to Jess Zimmerman’s perfect, gutting essay for Hazlitt from 2016, “Hunger Makes Me,” one of my bookmarked classics, when thinking about this particular shade of fear. Because shame has fear locked inside, I think, fear of being alive, of participating in life with your full filthy clumsy heart, of loving and being loved and failing and not failing. In this piece, she distills my own feelings in one of the most relatable passages I’ve ever read:

“Fearing hunger, fearing the loss of control that tips hunger into voraciousness, means fearing asking for anything: nourishment, attention, kindness, consideration, respect. Love, of course, and the manifestations of love. It means being so unwilling to seem “high-maintenance” that we pretend we do not need to be maintained. And eventually, it means losing the ability to recognize what it takes to maintain a self, a heart, a life.

So when I said “I don’t like romance,” it was the equivalent of a dieter insisting she just doesn’t want dessert. I did want it—I just thought I wasn’t allowed.”

And, later: “But asking to be thought of, understood, prioritized: this is a request so deep it is almost unfathomable. It’s a voracious request, the demand of the attention whore.”

Zimmerman locates this seemingly chronic and elemental anxiety, about our neediness, in patriarchal conditioning, in the learned affects of “womanhood,” and she’s right to do so.

It is cathartic, reassuring, to read pieces like these and to know that this shame did not originate with you, is not, in fact, like an extra limb—you weren’t born with the shame, it’s not yours to bear because of some incurable wrongness within you—and to name the systems that help engineer its omnipresence. Because even the women and femmes I know who aren’t, on the surface, constantly pulverized by shame, by guilt about wanting or needing too much, still tend to convey a shame in quieter, subtler gestures. So many of us socialized as girls might feel more capable of wanting and asserting a desire for sex, for example, but what about mutual respect, mutual pleasure, reciprocity both sexual and emotional; what about being cared for in a way even slightly above the bare minimum? It feels, yes, voracious. It feels greedy, maybe because we have been trained to believe in “girl power” but also to shrink and stay “girls,” in stature and feeling and needs, for our whole lives. It feels gluttonous because we associate hunger, especially femme-coded hunger, with something monstrous, ugly, unkempt, rather than what it is: HUMAN.

What if, for some of us, asking for romantic love, for the emotional intimacy and reciprocity and care and mistake-making involved, is the most subversive we can get? What if we—often because of the size or shape or appearance of our bodies, or not aligning closely enough with normative white beauty norms, or our queerness, or etc, etc—have been taught that such an experience, such consideration, is not ours to want, to have, ever? That we are lucky to catch crumbs. That the bare minimum, especially from men, is somehow revelatory, life-saving. That heteronormative and strict, patriarchal monogamy is the only script available. That we are frivolous or clingy or demanding or dumb for even desiring such intimacy at all.

I guess what I am saying, within all this mess, is that there is some power, in relinquishing control, in giving up the neoliberal fantasy of perfect self-sufficiency, of fetishized individualism and the new empowered ethos of Not Needing Anyone or Anything But Oneself. It is a tempting fantasy, I’ll admit, especially if you’ve been raised on shame since birth. It is a convenient dreamscape for us who want to avoid the potential devastation and assured-grief of love. But it’s also a fantasy, and a lifeless one. There’s no pulse. I don’t want to have to survive on it anymore.